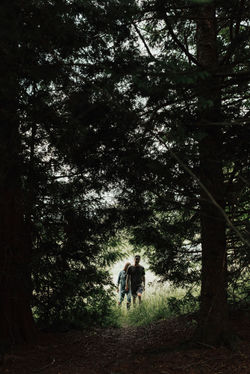

Images by Krystle Rakatu, Bespoke Photography

NICOLA & PAT

SLOW STREAM FARM

Sydney, Australia to Taupo region, New Zealand

To get to the lush grassy hillsides of Pat Ledden and Nicola Harvey’s Slow Stream Farm you drive just 15 km north of the seasonal tourist destination of Taupō, New Zealand. A waterway runs through their property and flows, eventually, into the Waikato river the main artery of Lake Taupō, and Mount Tauhara stands proudly above the landscape. The couple’s modest contemporary home sits just a short walk from their barns and pastures. It is here where their 300+ Hereford-Friesian & Angus cattle happily graze. Waking early every morning the couple makes their way to the barns to check on the calves and do morning feeding/watering rounds. It takes roughly four hours to complete their morning chores. Afterwards they head back to the house at 10am to have a second breakfast and coffee to keep them going. Nicola then attends to her freelance work for several hours while Pat works on their never-ending list of ranch projects. Their work days typically end around 6:30pm when they complete their final round of feeding together. “A good day,” Nicola confesses, “Is when we work our typical 10-12 hours and nothing goes wrong.”

While this new venture requires that they work seven-days a week and with much more physical labor than the couple is used to, it is a welcomed change from navigating corporate hierarchies and long commutes in Sydney. Before starting Slow Stream Farm, Nicola worked as a journalist. Her career had her working for various media companies and production houses in London, Melbourne and Sydney. She worked her way up the corporate ladder and landed the sought after Managing Editor position at Buzzfeed Australia. Pat worked as a property valuer and played guitar in bands. Sydney provided many cultural delights for the couple but they felt overly stressed and stifled creatively. They began dreaming of returning to the rural landscapes of their youth and building something together.

The couple had a softer transition to ranch life than most first-time farmers because Nicola grew up on a cattle ranch and Pat would spend school holidays on his grand parents’ property (Nicola in New Zealand and Pat in Australia). This isn’t to say that the last year hasn’t been a steep learning curve because, like many of their Australian and Kiwi peers, both left their rural homes in their teens to backpack around the world and attend university. It had been a solid twenty years since either of them had spent any real time away from city life. Luckily, Slow Stream Farm was a homecoming for Nicola, as her family has been raising animals on land in this region for several generations. Nicola’s father, nearing retirement, has been working alongside the couple to help them get up and running.

For Nicola, returning to her childhood home has been a welcomed rewiring from the glacially slow processes of the corporate world. “The fact that we are working for ourselves has made our decision making process light speed – we can action things quickly and we don’t have to run them by a million people.” Now that they have ironed out a lot of the kinks in their farming operation the couple has begun to brainstorm future creative projects. Pat would like to start playing music again and Nicola has been commissioned by Audible to produce podcasts with a former colleague in the city. They both are working on the initial ideas for a book that promotes food produced by regenerative agriculture practices.

With some of the strictest Animal Welfare laws in the world, New Zealand has been a pioneer in establishing a code of conduct for the ethical treatment of animals raised for meat and dairy products. “In the last five years there has been a sustained and really positive push towards a new style of farming,” Nicola says. New Zealand has taken the necessary step of connecting animal health and welfare to the farmer’s bottom line. “Older farmers with more conservative farming practices are making changes now because they are seeing the connection to increased profitability.”

In New Zealand and Australian consumer demand for meat is in the decline. “There is a big push for beans not beef,” Pat says. “New Zealand is an anomaly because our primary contribution to greenhouse gases is our agriculture industry.” Veganism is on the rise in both Australia and New Zealand as people are deciding to choose plant-based diets for both health reasons and to combat climate change. So why build a pasture-raised meat business in New Zealand? “Demand for ethically-raised meat from the U.S., Europe and Chinese markets, for clean green meat, is on the rise and very likely the catalyst for these new standards.” Nicola says, “Around fifty percent of New Zealand beef is sent to the United States.”

While some generational ranchers are feeling overly regulated by these new standards for animal welfare and environmental protections, Pat and Nicola feel like they are all steps in the right direction. Their primary goal at Slow Stream Farm is to create a sustainable and regenerative agriculture operation. Rich soil, clean waterways and healthy cattle – all of the elements of their land and farm living harmony with one another. (Click here to jump to their interview)

www.slowstreamfarm.com

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

What inspired you to move to the country?

Nicola: My Australian husband and I are both from farming families. For me that lineage runs five generations deep in New Zealand. I spent the first eight years of my life on a cattle, deer and sheep farm, but when we sold the property (in the ‘80s) my parents’ ambitions for me became focused on a “city profession”, something that would take me away from the small town where I spent my teens, and in effect the country I was from. So as soon as I was done with my university studies I was gone. First to Melbourne then London then Sydney. For 17 years I learned the business and craft of publishing, journalism and broadcasting and ended up as a Managing Editor (for BuzzFeed). But exhaustion was what I had to show for this dedication.

Pat: I moved to Sydney 20 years ago from a mid-sized town in regional New South Wales (Australia). I had a life-cum-career in music in my sights and the big city was where this was going to happen. As the years went on -- gigging, traveling, learning, making mistakes -- I hit my 30s and decided to go back to university to retrain as a property valuer, and then the corporate hamster wheel loomed: monthly targets, bonuses, late nights, and long weeks.

Living to work isn’t fun, and miraculously we landed on this realization at the same time. On a Saturday morning in September 2017, Nicola’s farmer father called for his weekly catch up. Most phone calls included a joke about how redundant we, the city slickers, would be on a farm. But on that day the conversation wasn’t funny anymore. What we wanted most was to awake and listen to bird song rather than bus breaks. That conversation prompted a new one for us, and questions started to flow: should we leave Sydney? Could we afford it? How do we do it? What will we do for work? After decades of striving for one thing -- career success -- could we just leave? In the end the decision was easy: we decided exhaustion was not the status symbol or measure of success we wanted. So our move to the country was motivated by a strong physical need to feel well again, to feel something other than tired.

Did you research a lot of potential locations before you moved?

We started looking at small commuter town options around Sydney long before we decided to relocate from Sydney to New Zealand. But every option meant 2-3hrs a day commuting, by train or car. We’d be giving up more time simply to live “in the country” in the weekend. And the grind would still be the same. Moving to New Zealand meant a massive upheaval, but it also came with a safety net -- we were given the opportunity to rent half of the 180 hectre farm Nicola’s father was running and live in the farm house. We decided to go all in and give up everything, the good and bad that defined our lives in the city. That meant no more full time employment, professional careers, long-term friends, live music, art galleries, festivals, craft beer breweries, commuting, and 60 hour work weeks at a desk.

Why did you decide to move to this particular rural part of New Zealand?

Nicola grew up in the Taupo region, and Pat has been coming here each summer for almost a decade so it was familiar. But more importantly it was affordable -- we didn’t have to buy land outright, we could start our farming careers and life on the land by simply renting land off Nicola’s Dad.

How did your friends and family respond to your plans of leaving the city and moving to the country to farm?

When we starting telling friends we were leaving Sydney to move to Taupo to run a small calf rearing and beef finishing unit most looked at us with sympathy or confusion.

“What the hell is a beef finishing unit?”, some asked.

Then a week later they’d “admit” they were a little envious.

“A house in the country?” Sigh. “That sounds to good… will you have chickens?”

Sydney is a city the breeds escape plans. People want out, but how to do it remains a mystery. Big life change requires risk, and vulnerability, and if you’re deep into the cycle with mortgages, credit card debt, child-care costs, a shopping habit, and a good salary to service it all the possibility of not affording the list can be terrifying. So most put the escape plan back in the drawer.

How did you learn to farm? Can you recommend any books, online tutorials, podcasts, etc. that have helped educate and inspire you?

For inspiration pre-move Nicola spent a lot of time listening to Krista Tippett’s On Being podcast, seeking out episodes that tackled courage and vulnerability. Moving country, changing careers, giving up full time employment is a big deal! And we needed some emotional and intellectual support. But it came mostly from Krista chatting to American sociologist Brene Brown and Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer not our friends and family, who had few reference points for what we were doing.

Once in New Zealand we had anticipated that our “farming university” would consist of Nicola’s dad, uncle, contacts and friends “showing us the ropes”. Most have been farmers or worked in associated industries for more than 40 years. But the reality was much different. We listened to the advice, and more often than not thought… “that doesn’t sound quite right”. So would cross reference everything that was said with published research and sustainability guidelines widely available online. But we focused on New Zealand guides ‘cause unlike many beef producing countries New Zealand rears and raises cattle outside. It’s a temperate country so we don’t barn our cattle, it’s almost entirely grass and crop grazing (bar some feedlots, which are a blot on the farming landscape).

Farming practices in New Zealand have changed a lot in the past decade, even more so in the past three years. Sustainability is now regulated, animal welfare is coded, and, increasingly, farming enterprises are looking to market products to a domestic and international consumer base who are environmentally and health conscious. So the paddock to plate process has become unflinchingly transparent. That’s a big change from the farming practices of yesteryear. Surprisingly for Nicola’s father, the learning process has been a two way street. As far as practical skills of calf rearing go, we’ve relied heavily on Youtube videos and guide books published by New Zealand dairy and beef boards such as DairyNZ, and agriculture suppliers like PGG Wrightsons. And we were fortunate to have advice and guidance from a group of local vets (VetPlus) who took the time to educate us, write health plans, and show us best practice calf care. We learn best by asking questions. Lots and lots of questions, and in an industry that has for a long time been quite conservative that approach is perhaps a little unusual, so the vets were incredibly generous with their time. Animal health and welfare is the foundation of our little enterprise so we wanted to get it right from the outset.

Initially what was the hardest part about making the move? What challenges came later?

One of the hardest challenges has been working with family. We’re both used to professional environments that are goal (and profit) orientated, but the “family farm” mode of operating is far more casual and “lifestyle” focused. So we’ve spent 10 months trying to find common ground that marries the family’s focus on lifestyle farming with our desire to set up new systems, challenge the status quo, and in time establish a sustainable operation that is professionally satisfying and profitable!

As for culture shock, we miss very little about the frenetic pace of the big city. But when the cravings for city luxuries (food, art, people watching) become too severe we head to Auckland or Wellington for mini-breaks or “research trips” as we like to call them. And thanks to email, Instagram and G-chat we’re still totally plugged into a network that challenges us intellectually (perhaps even more now that we have the time to properly engage with new research, products, info, insights) etc).

Is there anything you miss about living in a city? Would you ever consider moving back?

We miss good, spicy Vietnamese and Lebanese food. Sydney has the most amazing food scene thanks to Australia’s multiculturalism, and if there’s one thing that would draw us back it would be easy access to proper hummus and pho. In all seriousness though, we set out on this journey with a four-five year plan. We needed a break, and we needed to be inspired by something other than the city scape. And we’re getting that on a daily basis: the New Zealand bush, the fresh air, the landscapes, and joy of working with and learning about animals is rejuvenating. But that doesn’t mean we’re here for life. Who knows what opportunities might arise in five years time, perhaps we’ll have the best of both worlds -- living on the land with short stints in the city. We’re open to whatever life throws at us.

What advice would you give to someone thinking of moving out of the city?

Don’t go until you are 100% ready. It’s hard work living on the land, and city rules and processes don’t really apply. The pace may be slower but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have more free time. For a large part of the year we work seven days a week, and our work days are inevitably defined by the weather, our animals, and the seasons. We can’t control much of that. So be prepared to redefine what constitutes work, and be open to experiencing new forms of pleasure and career satisfaction.

Where do you draw your inspiration and passion from for your work?

In the immediate sense we draw our passion from our animals. Our calves are curious and playful little things, and their energy can be infectious. In a more holistic sense we’re inspired by the small but regular changes that are happening in our new industry. People are starting to really fight for better farming practices, healthier food, more information, better land management, more transparency… and it’s coming from both within the industry and from consumers. The shift is needed because we can simply barrel long using the planet’s resources in the way we have for the past 50 years.

Walk us through a typical day at Slow Stream Farm.

We have two peak seasons of work each year, the Autumn (Fall) and Spring calf seasons. And when we’re in the calf tunnel the days and weeks are long. A typical day starts at 5:30am with espresso coffee (sourced from our favourite local roasters at Bubu Coffee!). By 6.15am we’re usually pulling on our boots and heading for the farm sheds, a 5min walk through the trees at the back of the house. Then starts the feeding routine: mixing milk for 150-250 calves, feeding each lot either in the shed if they’re young or in the paddock if they’re a little older. We give each calf a daily health check, then distribute meal and hay, and clean all the water troughs. We clean or replace the bedding in the shed each day, and scrub down the railings and gates. Cleanliness is the thing that will keep our calves healthy. Then it’s more cleaning -- all the mixing and feed equipment while Pat goes off to check the older cattle with our dog Red. If it’s deep winter we also feed hay to the older stock. If all goes well we’re usually back at the house by 10.00, via the chicken coop to collect eggs, for another coffee and second breakfast. Then we might head off to one of the nearby dairy farms to collect the next lot of calves. If we’re doing a pick up we’ll spend time with the new calves observing them, and ensuring they’re healthy. By noon, Nicola is usually at her desk starting her “other job” -- as an executive producer for an Sydney-based media company. For most of 2018 she worked five-six hours a day developing and co-producing podcasts and video film projects, and wrangling contracts and paperwork for BuzzFeed Australia.

In Spring, we were feeding our younger calves twice a day so we’d repeat the morning routine. By 6:30pm we’re typically done. This was the routine seven days a week from April through to June, and August through to November. It’s a lot, but it’s manageable. We just made the decision to keep going. In 2019 the pace will be slightly easier ‘cause we’re reviewed out calf feeding processes to make it less labour intensive, and Nicola is working short term project contracts rather than near full time. On we go!

If you could time machine back to the early stages of building your farm business, what advice would you give yourself?

Everything takes longer than you expect, so don’t over commit! We had to keep reminding ourselves that we moved away from the city to slow down, but that didn’t really eventuate in 2018 until we hit summer… some 10 months after we made the move.

How did you/do you overcome any feelings of uncertainty and fear when it comes to making decisions and taking risks?

We’re both really pragmatic people, so very few decisions are made on gut instinct or a whim. It sounds really nerdy but we tackled the fear and uncertainty of this new venture by running risk analysis, creating variants of our business plans, doing tonnes of research, asking loads of questions, and by trusting each other. The final point is the most important. This new life, and new business won’t work if we, as a team, break down.

How important has your local community been to the growth and success of your business?

We’re very much in the early stages of our new business so it’s hard to quantify success. But without question the small handful of local farmers who have gone out of their way to give us advice and assistance have been vital. Some have simply offered us free hay when we most needed it, others have become trusted partners who we work with throughout the season, and all have been welcoming and generous (if not a little bemused at times ‘cause we don’t look like farmers). But equally important for our morale are the local business owners who we initially met via Instagram. It’s this group, who share our world view and some of our ambitions, who cheer us up at the end of a long week and keep us focused on the big picture. Check them out on Insta! Indent Journal (publishing), Lush Lane (plants), Storehouse (cafe), Bubu Coffee (coffee roasters), Bespoke Taupo (photography).

What techniques and channels have proven the most successful in marketing to new customers and growing your business?

As mentioned, we’re not yet in a position to start marketing to new customers and we’re also not 100% certain what shape or form that product will take. But our fledgling businesses are in good shape after the first year. Slow Stream Farm, our calf rearing / beef operation, was built via word of mouth. New Zealand farming is still old fashioned in the sense that many business deals and new ventures are brokered verbally, via an introduction made by someone who’s been in the game for a while. Contracts or email chains are hard to come by. At first that can be off-putting ‘cause it’s hard to break in. But a spirit of generosity abounds once you start having the conversations and we quickly learned who to trust and who to avoid (there’s still a lot of people farming for profit only and we wanted to stay clear of their shoddy practices). When the time comes for Slow Stream Farm to start selling our produce we’ll start local. There is precedent for this in our region with a farming collective Taupo Beef & Lamb. They work with an independent producer that sells under the label Harmony. They’re dedicated to ethical and sustainable production, with a particular focus on water protection -- and that’s exactly that ethos we’re applying to our operation.

Have you been able to build a good community here in the country?

We’re getting there, but it’s slow going. Now that summer is here and we’re not working seven days a week we’re starting to meet more like-minded people. But the region we’re living in -- north of Taupo -- is not renowned as a foodie destination so we’re looking for inspiration and contacts elsewhere in New Zealand: in Hawke’s Bay, the Wellington district, and around Auckland, where the culture of sustainable food production is more established.

Do you notice a trend in New Zealand of young people leaving city life behind or does it feel more like people are flocking to the cities in search of a better quality of life?

There has been a noticeable shift away from the big cities, especially Auckland, in the past three years. This shift is in large part fueled by exorbitant property prices in Auckland, it’s been hard for young people and families to find affordable homes to buy or rent. So many have looked to smaller cities and towns, like Taupo where we’ve landed. The impetus for the move may be property but increasingly that comes with a desire to live a slightly slower life than what is possible in a big city. New Zealand is a progressive society, and people are quick to support local business and local food production. That built in consumer base makes it easier for people like us to start new ventures, which makes moving away from the main urban areas all the more appealing.

What is your favorite place on your property to retreat to when you’ve had a challenging day?

We have a double seater on the patio that looks over the tributary our farm is named after, and it’s become our breakfast spot. From there we can watch the birds what live on the lake at the bottom of the house paddock. We have a resident hawk that regularly hunts for rodents (stoats and weasels -- both introduced species that are killing our native birds) in the rushes around the lake. The hawk’s daily routine is a useful reminder that nature is both peaceful and brutal, and that we are just part of the bigger system.

What are some common misperceptions about life in the country? What do you want people to know/understand about life in small communities?

A common misconception is that it’s isolated, and disconnected from the epicenters of culture. In truth, time spent living in the country or in small communities, especially in the age of the internet / social media, can spawn the culture that comes to define big city living. This is especially true of the food industry (think farmers markets, nose to tail eating, raw food movement) but also for media and entertainment -- the other part of our professional lives. Some of the best storytelling has its source in small town life and ritual.

What are your future plans/goals for the coming year?

2019 will be a big year for Slow Stream Farm ‘cause our first season calves will be nearing a weight for either on-sell or butchering. We’ll need to answer some big questions: do we establish our own label to sell under? Do we join the local sustainable beef collective? Do we sell to a bigger operation and loose the value of our sustainability ethics?

And, of equal importance we’ll be releasing a podcast titled 9 Billion Mouths under Nicola’s production company Pipi Films. The series investigates some of the big food questions facing consumers in 2019.

In general, the training wheels are coming off and we’re excited to learn more about sustainable farming, to share the stories we’ve collected along the way, and to do more and better each day so that we leave this land we’re working in a better condition than when we started.

_____________________________

BACKGROUND INFO ON TAUPO

Taupo is a small town of 25,000 located three and a half hours south of Auckland in the north island of New Zealand. It’s a renowned tourist destination due to the town’s location on the edge of Lake Taupo, the largest in New Zealand. At the south end of the lake is the Tongariro National Park, home to Whakapapa and Turoa ski fields. It’s an outdoor adventure destination with mountain biking, trout fishing, hiking and skiing facilities all within a short drive from Taupo town.

Taupo’s farming industry is mainly focused on dairy, beef and forestry. The region is volcanic (the lake is literally a dormant volcano, and the mountains at the end of the late are still active) which means the soil isn’t well suited to some NZ’s most profitable / well known horticulture industries such as grape growing and wine making, kiwi and stone fruit orchards. It is, however, a hotspot for Manuka trees, the source for NZ’s Manuka honey.

Over the past decade environmentally-conscious councils have introduced water management policies intent on managing farm-derived water pollution. New Zealand has a booming dairy industry, and an increasingly water-quality issue. The two are related. In Taupo, the water quality of the lake is of utmost importance which prompted the local council authority to introduce in 2011 an environmental protection symbol for farms that abide by sustainable anti leaching practices. In short, nitrogen runoff from cattle (Dairy and Beef) was or is changing the water quality. Higher nitrogen levels = major impact to the lake’s ecosystem. Farms that adjoin the lake are now required to meet strict land use rules, which include a lower stock rate than almost anywhere else in the country. The upshot though is that the plan, first mooted in the ‘90s, is working and the Lake’s water quality is improving year on year. Water quality is a country-wide issue and has pushed the farming industry to develop sustainable practices that are in turn being used to market NZ food products as “clean, green produce”.

Taupo sits on Ngati Tuwharetoa land, the local Maori (first nations) tribe. New Zealand is a bicultural country and much land management policy is developed through the prism of first nations knowledge. This leads to an ethos of guardianship. New Zealanders for the most part believe that our presence on this land, and our use of resources, needs to be modulated by a goal to preserve and protect for future generations.

Slow Stream Farm work with Ngati Kapawa (part of the Ngati Tuwharetoa tribe) to rejuvenate the waterways that run through the farm. A five-year project to plant endemic flora along the waterways is currently underway (flax, manuka, totura trees etc). Local Maori have right of access to these waterways to collect food.

HERE ARE SOME OTHER STORIES YOU MIGHT LIKE...